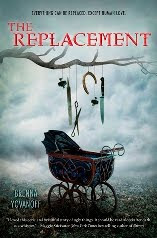

This is a bit of an experimental two part discussion on Brenna Yovanoff’s 'The Replacement’.

This is a bit of an experimental two part discussion on Brenna Yovanoff’s 'The Replacement’.Today’s post consists of an essay type post that begins with a plot synopsis, then goes on to look at an idea present in the book and follows my thoughts surrounding this idea. Then at the end there’s a bit of evaluation on how well the book deals with this and other ideas.

Tomorrow’s post will be a chatty type post which assumes a bit more knowledge of the book, looking at what I think are the most best aspects of ‘The Replacement’. It won’t use an essay structure and it will be more freeform.

Please let me know how you find this experiment. I’m really trying to find a way to reconcile my critical monster, which is all about picking things apart and going ‘Oooo is that how that works?’ and my love of many books.

‘In the story, Emma’s four years old. She gets out of bed and pads across the floor in her footie pajamas. When she reaches her hand between the bars, the thing in the crib moves closer. It tries to bite her and she takes her hand out again but doesn’t back away. They spend all night looking at each other in the dark. In the morning, the thing is still crouched on the lamb-and-duckling mattress pad, staring at her. It isn’t her brother.

It’s me.’

It’s me.’

Mackie is a replacement. The real Malcolm Doyle was stolen when he was a baby by the fey creatures that live under the slag heap in the steel town of Gentry. Mackie was left in his crib to grow up as a normal child with the Doyle family, but he’ll never be human. Usually replacements die at an early age as they’re intolerant to the iron in the human world (replacements being Brenna Yovanoff’s version of fairy/elvish changeling babies), but Mackie survives thanks to the family’s care, especially the love shown by his sister Emma. It’s not easy to be a replacement, masquerading as a human, but Mackie does his best to fit in and make human friends while avoiding contact with the world under the slag heap.

Then Mackie comes to the attention of Tate, a girl at his school whose sister has just died. Tate insists that whatever they buried wasn’t her sister. She thinks he sister has died elsewhere, snatched and killed by the same things that brought Mackie. She asks of Mackie is that he acknowledge the truth of replacements, but admitting what he is to an outsider goes against everything Mackie has been taught so he refuses.

Meanwhile Mackie is becoming more intolerant to the iron in the world, which pushes Emma, his devoted older sister, to make contact with the world under the slag heap to get him a potion to help him survive. Both Tate’s contact with him and Emma’s contact with the fey propel Mackie into the world of The Morrigan and The Lady, the two fey sisters who run different factions of the fey community in Gentry (although The Lady ultimately controls the whole lot). When he finds that Tate’s sister may not be dead yet Mackie has to decide how involved he can safely get in the world of the fey.

The people of Gentry deliberately avoid seeing what Mackie is and what is going on around them. People are aware that children are occasionally replaced, but they choose not to engage with the reality of the folk under the hill unless forced to, because in exchange for their children Gentry remains prosperous as other industrial towns collapse. The idea of a town grown prosperous through such an inauspicious relationship was I think, vague and under developed, but I found the idea of being willingly deceived an interesting theme. I’m used to seeing fantasy novels address the idea that everyone contributes to their own deception; it’s a classic idea that can produces a lot of mental satisfaction in my readerly brain because of the twisty angles it can push plots. What intrigues me about Brenna Yovanoff’s examination of willing deception is how many layers she puts into this idea by showing Mackie, the ‘monster’ character being co-opted into the deception by ordinary people, rather than being the originator of the deception.

The people of Gentry need to make Mackie take part in their deception if they’re going to be able to deceive themselves that nothing is wrong in their town. Mackie is required to publically conceal what he is if the townspeople are going to plausibly deny the presence of child stealing monsters to themselves. If they are forced to admit they know what Mackie is they would have to take action against the child stealing, or face their lack of action honestly. So, the towns people covertly, subconsciously help Mackie to maintain his deception of them so that they don’t have to deal with the truth. By hiding from the obvious knowledge that Mackie is like the fey creatures, they indicate to Mackie how he is expected to act. Crowd persuasion can play an important part in convincing anyone that a certain way of living is normal and Mackie sees how others deny the truth of Gentry and him and works at fitting in with other people’s version of normal living (a kind of living that turns on lies and self-deception) by hiding his heritage. He is also terrified that if he deviates from what the town has set up as normal life he will be punished, especially as there is precedent of a fey creature who revealed himself being killed.

The precarious mental state that the people of Gentry maintain, balanced between an awareness of what Mackie is, as well as what his existence means and a determined repression of that knowledge, makes Mackie’s time among them terrifyingly uncertain, as someone could decide to notice what he is at any time and punish him for any kind of misfortune that hits Gentry. To avoid spending all his time rocking in a corner waiting for Gentry to recognise him and hang him as a dangerous monster, Mackie is required to uphold an internal pretence that his deception of others is successful and that his safety depends on continuing to lie. His father’s repetition of a story about Kellan Caury who was hung when children started to disappear initially sounds like the morbid warning of an overly protective parent, but can also be seen as an attempt to reassure Mackie and his father that they have some control over Mackie’s safety:

‘The moral of the story is, don’t attract attention. Don’t have deformed fingers. Don’t let anyone know how amazing you are at tuning string by ear. Don’t show anyone the true, honest heart of yourself, or else when something goes wrong, you might wind up rotting in a tree.’

This story (that we’re told is repeated often to Mackie) of who reveals himself and dies, provides Mackie’s dad with a reassuring myth of control in the same way that burying replacements as their kids without making a fuss reassures the people of Gentry that monsters do not exist. As long as they hide Mackie’s fey traits like his talent with instruments and his aversion to iron they can keep Mackie safe. It was Kellan Caury’s visibility that got him lynched. There is action they can take to keep Mackie safe. In reality Mackie’s lies only works as long as the town agrees to be deceived. His heritage is visibly obvious to anyone who decides not to participate in the collaborative performance. His father’s pretence of control, covers up fact that Mackie’s safety is something that he cannot control without the willing involvement of other liars, like the townspeople.

So readers can see that Mackie’s mental state is just as precarious as the townspeople of Gentry. Caught between wanting to believe his own lies, wanting to be himself and just wanting to be normal. The difference between Mackie and the townspeople is that Mackie can never lapse into the passive fantasy of a normal life, like the human characters. There’s too much painful evidence that keeps him from pretending to be normal, for example he can’t walk on consecrated ground (tricky as his dad is the town’s minister). While Mackie never quite accepts that he can control his own safety, because he’s so aware of himself and how obviously he stands out, lies and avoidance are the only coping mechanisms he has. When human character Tate decides to stop being passively deceived, because her sister has been stolen, Mackie holds on to the idea that he can still hide in plain sight without the co-operation of the person he’s hiding things from. Here he becomes the deceiver, but Tate’s insistence that she knows he can help her sister proves that he can’t sustain the illusion of normal without help from others. The townspeople have to collaborate in creating normality for Gentry to seem normal and with their determination to project normality they doom themselves to lies and oppression.

As Mackie is the character given a first person narrative the reader is given ready access into the conflicts of the ‘monster’ side of this mental conflict. Mackie is the character that we see struggling most immediately with the difficulty of believing in the power of his lies when he really knows that they are ineffective safeguards. The tussle between lies and truth is less immediately apparent in the human characters, who do not reveal their inner thoughts through direct narratives. In contrast with the access readers have into Mackie’s troubled thoughts, this lack of access into the townspeople’s thoughts makes the people of Gentry feel contented in their deception and almost cruel, as if they are the ones who force the deception on Mackie, rather than being the victims of the people living under the hill. The townspeople’s more complex mental conflict creeps through as readers are introduced to characters like Tate, Jenna, or Mackie’s mother and later when readers are introduced to the villain of the book the people’s victimhood becomes obvious, but for the first half of the book Mackie is the one readers will be concerned about, rather than the families who get their kids snatched. Do the people of Gentry appear as Mackie’s oppressors, more than victims? Divided opinion in my head – maybe the creepiness of the general tone of the book got under my skin and I started viewing everyone (outside Mackie’s immediate circle of friends) as having a bit of a cruel streak, so framed the town as an oppressor...in fact that’s probably it, because there are lots of people in Gentry who do care about Mackie and try to help him even if it means acknowledging the truth of what he is. I think there’s little textual evidence to say that the townspeople are deliberately cruel in their desire to keep Mackie from being able to be himself, but there is an aura of casual cruelty that attaches itself in my mind to the whole town and not just its fey population. Maybe it’s Alice, the mean girl character Mackie has a crush on that makes me feel that way. She seemed strangely knowing to me, as well as being horrible.

Like I said I was going to, I’ve given a lot of space to the idea of one idea in ‘The Replacement’ (how deceit is created by characters, as much as it is forced on them – hopefully it all made some sense). Although I think ‘The Replacement’ has great potential for being a book full of big, deep ideas, I think it often resists giving a coherent shape to its ideas within the text. The exploration of how people deceive themselves is the one idea that is fully explored within the text. Readers have to do a lot of extrapolating and personal reading to get to other ideas and to form a shape that means something more than the literal meaning of a few pieces of text. Yovanof introduces lots of little important concepts, for example Mackie’s sister Emma puts forward her conflicted feelings about nurturing a brother who then exceeds her in beauty, but still remains extremely vulnerable, but these ideas feel scattered and unresolved within the text. I mean they don’t follow a linear progress of problem, thoughts, circle back to reinforce idea/possible concrete position on ideas... so readers might feel lost as to where the author wants to direct their thoughts. The ideas, often drawn from the inclusion of an element of fey legend, feel incomplete, cast off as soon as they’re mentioned and I think that attempts to return to these ideas later in the book sometimes force the plot to move to new areas before it’s ready. The result is some powerful static scenes, like Mackie’s moment on stage with a fey band and his father’s church setting on fire, that make the book jerk around jarringly (I know, so technical, imagine a sudden cutaway in the middle of a film mostly about a road trip or something).

Whether my feelings that the different ideas are scattered, too many and compete with each other indicate a structural flaw in the book, or my inability to concentrate on this kind of different idea dispersal I couldn’t tell you. I do think Yovanoff comes close to pulling of another complete idea in later parts of the book when she has The Morrigan and the Lady represent different perspectives on how gods lose their power and can be sustained through worship.

I do think that ‘The Replacement’ resists being read directly as a metaphorical text where the lessons from Mackie’s life as a replacement can be transferred on to general human concerns. There’s subtext that can be pulled out (personally I’m seeing a little bit of GLBT subtext) and related to ordinary life, but I don’t think the subtext was designed to be specific. While many paranormal stories are keen to make specific links between paranormal situations and real life (I’m thinking of Pratchett and conflict between trolls and dwarfs standing for racial tension, but there are hundreds of other examples) readers of ‘The Replacement’ will need to configure what real life issue they think the subtext relates to. I suppose what I’m saying is it’s not clear that the author was writing with anything but Mackie’s immediate reality in mind. Ultimately I think ‘The Replacement’ strives to be a piece of intricate storytelling, with strong plot, characterisation and world creation, rather than a novel of storytelling and big ideas (although I know I am now in the dodgy area of author intent) and that it is mostly a wonderful package of those things.

Check my thoughts tomorrow on all those areas.

Tags: